Intro II: A Few Tips for Coding (or Say Big Data One More Time)

Being a programmer means feeling stupid all the time, but less stupid than a year ago.

David Christiansen

Before we get started with R it is worth spending just a couple of minutes thinking about why we’re spending our time learning a programming language in the first place. Writing code is really about creative problem solving. We have some problem - maybe we want to analyze an interesting dataset or scrape some data from the web - and we write code to help us solve that problem. Problems usually have constraints. Common programming constraints include the inner workings of the programming language, platform, performance, etc. When working with code, we can define problem solving as writing a piece of code that performs a particular set of tasks given a set of constraints.

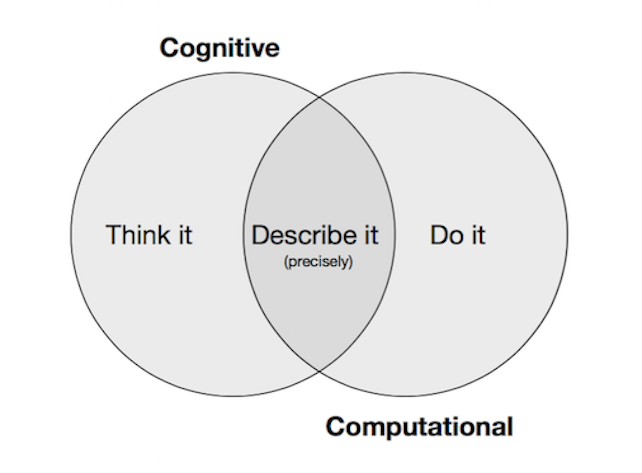

Writing good code often involve trading off two types of constraints: cognition time and computation time. Hadley Wickham, author of many great R packages, describes a data analysis workflow as follows

Before we write any code we need to think about the problem (for instance, how should our data look if we were to perform a particular regression?) and we need to describe exactly which steps are needed to achieve a given solution. Both steps can be done without opening your computer and writing one line of code, and they primarily involve cognitive constraints. When we’re done thinking, we need the program to execute our code and deliver the output. How fast and reliable this is done we can call the computational constraint. One simple way to think about the difference between big and small/medium sized data is as follows

- cognition time > computation time: you’re dealing with small/medium sized data

- computation time > cognition time: you could be dealing with big data.

Although we will spend significant time learning how to code in R, we will always focus on minimizing the cognitive costs of doing data analysis. When you’ve learning some sound principles for storing and working with small/medium sized data you’re better equipped to minimize computational costs as well.

So while this course will be technical and have a steep learning curve, we will not be dragged into the big data hype without a fight

A few tips

In the next post, I will introduce the basics of R. Before we get that far, however, here are a few tips for writing good code that you might want to think about in the rest of the course

-

code is plain-text: we will write all our code as plain-text files. Basically, that means that our files should be readable without any processing. This is different from formatted text, where style information is included. Microsoft Word is an example of the latter. It is practically impossible to open a Word file in any other program than Word. This is because the file includes style information that Microsoft Word has to render in order for the program to be readable. Plain-text files can be read or opened by any program that reads text and, for that reason, are considered platform independent. R scripts are basically plain-text files, but the convention is to save them with the extension

.R. -

style guides are important: good coding style is like using correct punctuation, and as with styles of punctuation, there are many possible variations. Everything is likely to be confusing when you’re learning a new programming language, so try to make a habit of writing as clean code as possible from the beginning. We will follow this style guide when coding in R. Among other things, that means that

- variable and function names are lowercase

- files that need to be run in sequence are prefixed with numbers

- nouns are used for variable names and verbs for function names

-

be lazy (write functions): one of the key points of learning R for data analysis is that allows us to be lazy by writing functions. So every time you copy paste some code in the same script you might want to stop, write a function, and call that instead. Functions in R are a group of instructions that take inputs, use them to compute other values, and return a result, and you will learn much more about them in the next posts.

-

prepare for frustration: learning new skills is always a frustrating adventure. This is true for everything you will ever do, but remember that if you’re not frustrated when learning a new skill, you’re probably not stretching yourself enough mentally. Or, as Hadley Wickham puts it

The bad news is that when ever you learn a new skill you’re going to suck. It’s going to be frustrating. The good news is that is typical and happens to everyone and it is only temporary. You can’t go from knowing nothing to becoming an expert without going through a period of great frustration and great suckiness.

References

This post builds on thoughts and ideas from Jenny Brian’s Stat 545 course, V. Anton Spraul’s Think Like a Programmer, as well as Hadley Wickham’s Advanced R book.

If you’re interested, and want to delve deeper into coding and programming (you certainly don’t have to, they are not required for this course), I highly recommend the following

- What is Code?: Paul Ford explains the workings of a computer in Bloomberg Business

- Think Like a Programmer: V. Anton Spraul’s book about creative problem solving with code.

For a fun, alternative, and provocative essay on programming I enjoyed reading Programming Sucks.